25 May Understanding Connected Speech in English for Improved Fluency

What is connected speech in English?

When we speak, we don’t pause between words. Words knock into each other. When we speak at a normal everyday speed, we find ways to make fast speech more efficient. Words link up in this way in every single language in the world, we’ve just got to learn the rules for how to do it in English. Some of the connected speech rules that apply in English might be the same as the rules that apply in your native language. Some of them might be different. But when you know how to join words more effectively, you’ll sound much more nativelike and you’ll be able to speak more quickly too. This is important because the more fluent your speech is, the more efficient your communication will be.

Mastering connected speech techniques for natural English pronunciation

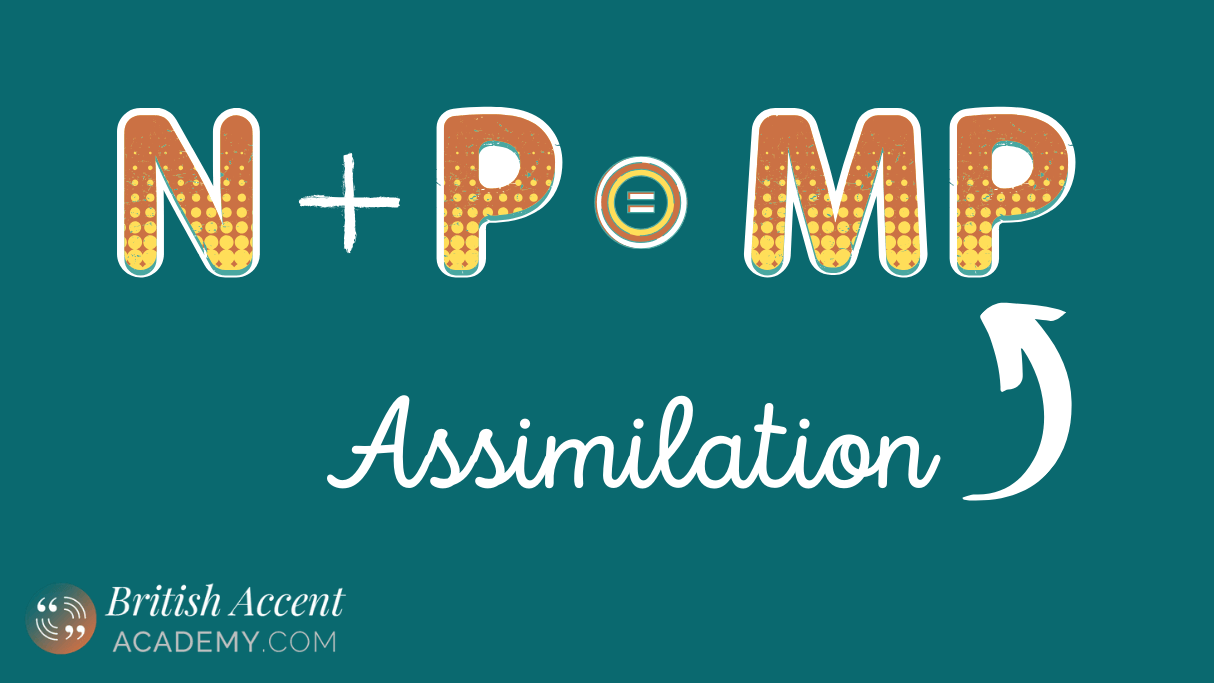

Assimilation in British English Pronunciation

In phonology, assimilation is when a speech sound becomes very similar to or the same as a neighbouring speech sound. In English, we see anticipatory assimilation where we change the place of articulation of a consonant phoneme to get ready for the next consonant phoneme. For example, if the nasal phoneme /n/ comes before /p/, the nasal consonant transforms into [m] because it’s much easier and more efficient to move from [m] to [p] than from [n] to [p]. [m] and [p] are both produced using the two lips so the lips are already in the right position for the [p] after the [m]. The pronunciation of <n> as [m] therefore makes sliding from the nasal to the plosive much more efficient and facilitates fast articulation. We say “[ɪm] Paris” and not “[ɪn] Paris”. Many speech sounds behave in this way in English. Learn all about assimilation in the Complete English Pronunciation Video Course!

The Phenomenon of Epenthesis in English

Epenthesis is when we add a speech sound that wouldn’t normally be present. When we say <fool>, <school>, and <stool>, we might add a little [ə] before the dark l [ɫ] to help us get our tongues from a fairly far back position to the alveolar position that the tongue tip needs to achieve for /l/. This addition of a new speech sound might help us to articulate words more clearly but it’s important to note when native speakers add speech sounds to facilitate rapid speech and when this is best avoided.

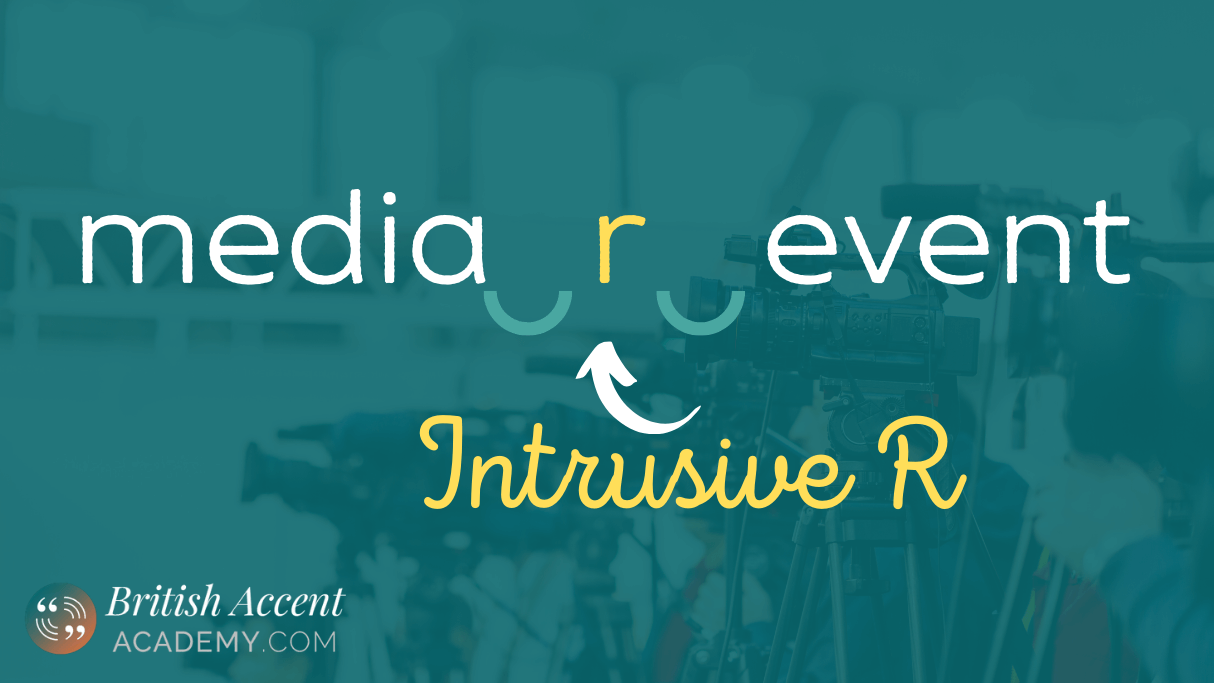

Intrusive R in British English: Understanding and Usage

British native speakers are often found to insert the alveolar or postalveolar approximant [ɹ] between vowels where there is no letter <r> in the spelling. While this is considered by some to be a mistake, almost every native British English speaker does this when connecting a word ending /ɔː/ or /ə/ with another word that begins with a vowel. Word endings such as <a> and <aw> often bring about this phenomenon. We regularly say “spar and massage” and “lawr and order” instead of “spa and massage” and “law and order”. If you’d prefer not to emulate this, that’s completely your choice, but if you’re keen to sound like an English native speaker, it can be useful to copy little tricks like this here and there in your daily speech.

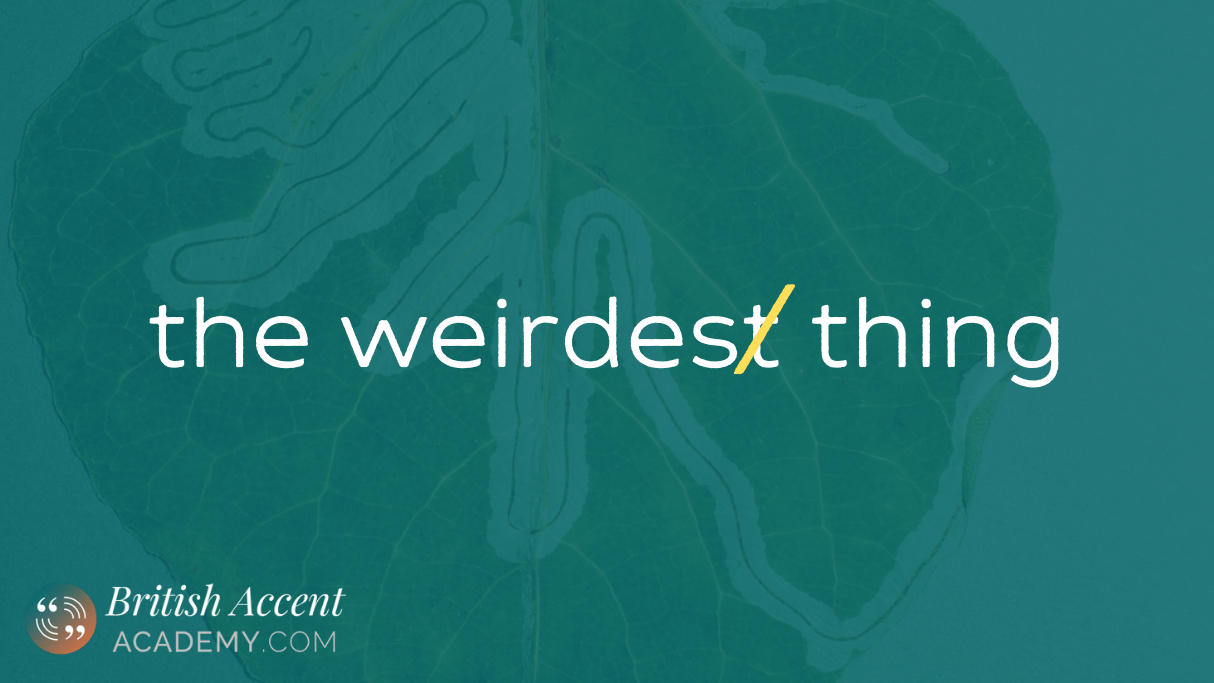

Elision in English pronunciation: when to delete sounds

Finally, let’s explore the phenomenon that phonologists call “elision”. Elision is the deletion of speech sounds in connected speech. A common example of elision can be found in the Complete English Pronunciation Course. In the phrase “the weirdest thing”, the letter <t> in “weirdest” comes after the fricative <s> and before another consonant phoneme. In this context, /t/ is deleted. Again, if you’d like your English to sound more nativelike, I recommend copying this pattern, deleting /t/ after /f/ and /s/ when /t/ comes before consonant phonemes. If you accidentally pronounce /t/ in this context, it will just sound very precise – it won’t be problematic. However, the more little native speaker tricks you can fit into your own English, the more compliments you will get on your clear and nativelike accent. Give it a try!